Own your newsfeed, own your data

A guide to keeping all your news sources and items in one place

We all have things we care about and follow. Whether it’s sports, arts, technology, from the mainstream to the obscure, we gravitate around them. Over time, we tend to both specialise, accumulating knowledge in specific sub-domains, and expand, jumping to adjacent topics or adding new ones to our list. Over time, we all become some kind of expert in something.

This is also true when doing research. Many journalists, for example, are not really experts in the domains their research takes them. Gradually, however, they have — hopefully — developed the ability to start from scratch, identify information sources, fact check them, weigh them against each other, and use their judgement to form conclusions and opinions.

This process of acquiring “temporary expertise” is particularly relevant at times like these. Unfolding situations in previously unknown domains like epidemiology, which COVID-19 has brought to the limelight, calls for an organised approach to news consumption to be able to cope with the volume, variety, and velocity of the information thrust upon us.

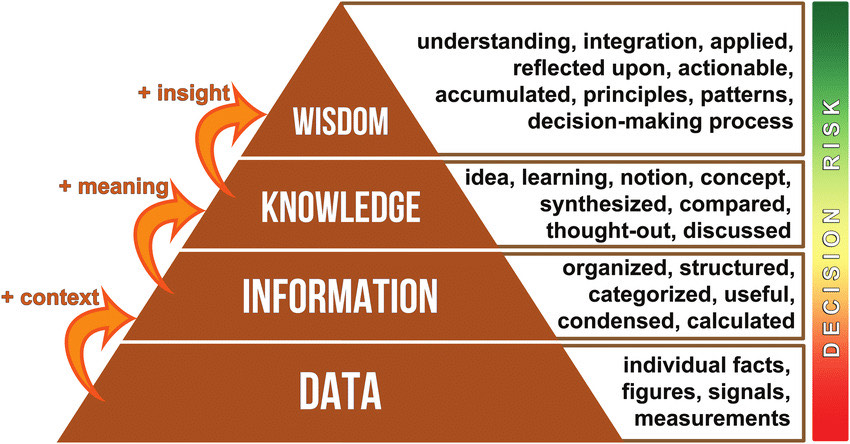

Essentially, we’re looking at big data on the individual level. The quest to go from data to information and ascertain some kind of knowledge out of the process calls for a structured approach to news consumption and research.

Most people, however, don’t systematically keep track of the news items they consume and the sources they get them from. Relying on search engines and social media not only to find and consume information but also to store and share it is problematic for a number of reasons.

Besides data sovereignty, filter bubbles and the like, functionality-wise, social media are not well suited for knowledge management. They lack even basic features such as categorisation and search. Search engines are somewhat better in that department, but you still have to rely on a third party to rank information for you, and over time, it becomes harder and harder to locate it.

So what’s a data journalist, or just the average person who wants to stay on top of the news, to do?

We’ll describe a structured approach to news consumption and management. We will outline the principles, and show how they work using specific tools. The main idea is to use standards and techniques that ensure interoperability, so you can implement the principles irrespective of tools.

Own the newsfeed: why, and how, to organise and aggregate all your news in one place

Despite their shortcomings in terms of knowledge management, social media offer important benefits too: curation and commentary. We rely on people we follow to provide curated news, as well as their own views and comments, because they can add value to the news. In other cases, however, we’d just like to have straight news, right from the source.

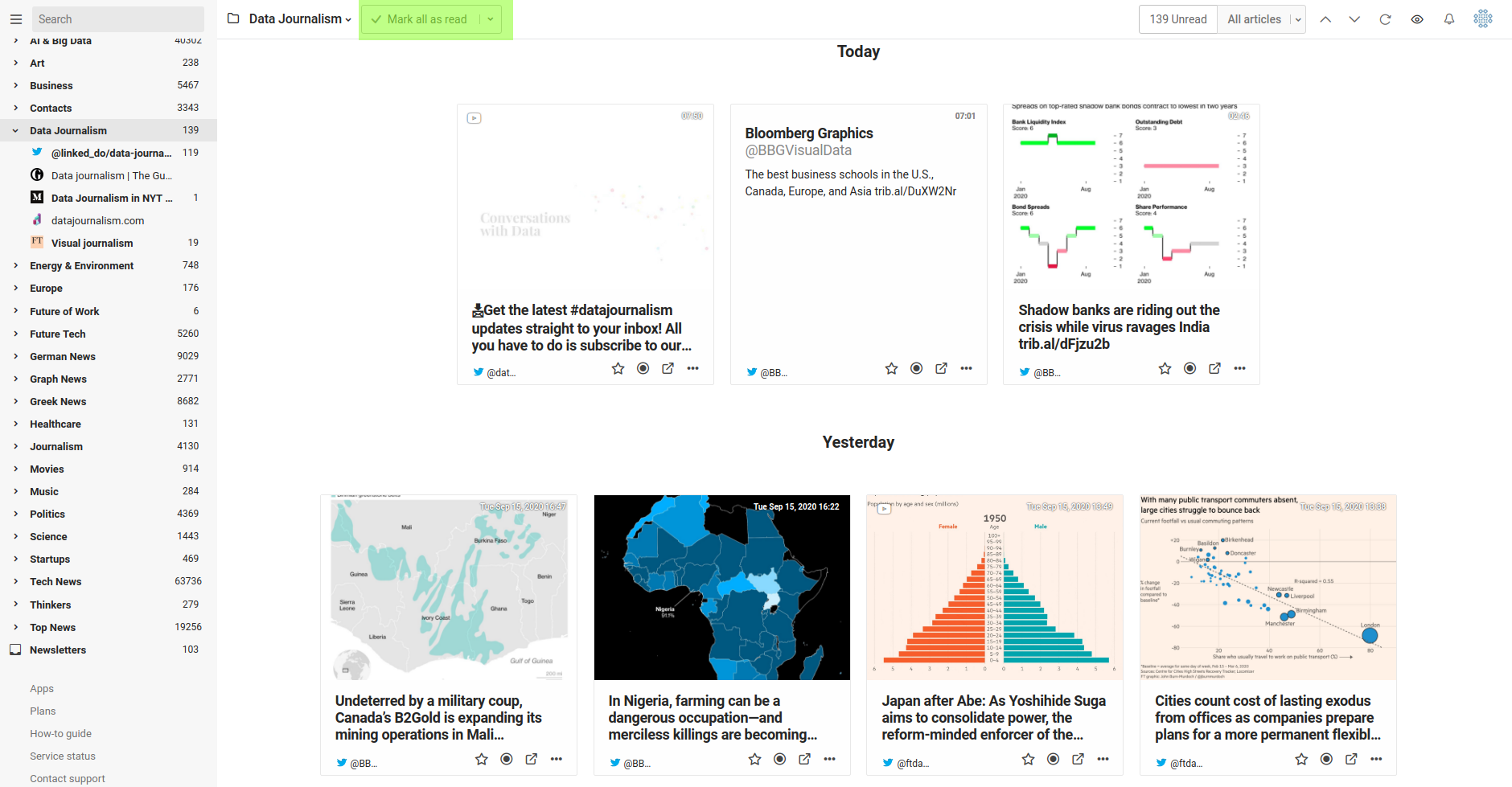

In both scenarios, we select and categorise our sources, whether explicitly or not. If you’re interested in Arts, Politics, and Technology, you probably have certain sources you regularly follow on those topics. The first step to an organised knowledge management process is making a list of topics you are interested in, and sources you follow for each of those.

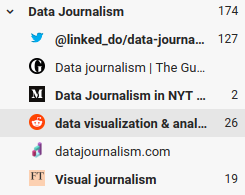

Beyond an exercise in self-discipline, this has very real ramifications. It can help organise newsfeeds, bringing order to chaos. One way some people do this today is by adding sources they follow on Twitter to Lists. Twitter, to its credit, is the only social medium that offers this. The idea, however, is an old one, going back to RSS.

RSS stands for “Really Simple Syndication” and was introduced by Netscape in 1999. Similar to social media, RSS sources offer their content as a feed. The difference is that users are in control: they decide what sources to subscribe to, and because RSS is standardised, they can subscribe to anything, and take their subscriptions with them.

RSS is a standard supported by most web sites, enabling compatible reader software to get notifications as soon as new content is available. Notifications include summaries and articles that pique one’s interest can be retrieved in full and read within the reader software.

RSS is a better way of monitoring sources, because it’s standard, and offers benefits such as storage. This is why it’s better to add your source’s RSS feed, rather than its Twitter account if you have a choice. Twitter is good in cases you want to follow individuals without a permanent home for their publications, for example.

Users can subscribe to sites they want to follow, and they can also organise their subscriptions in Folders. So if I want to keep up with my favourite art critic, the literary section of the paper I read, and be in the know about upcoming events in my local museum, I can subscribe to their pages, and keep them all in a Folder called Arts.

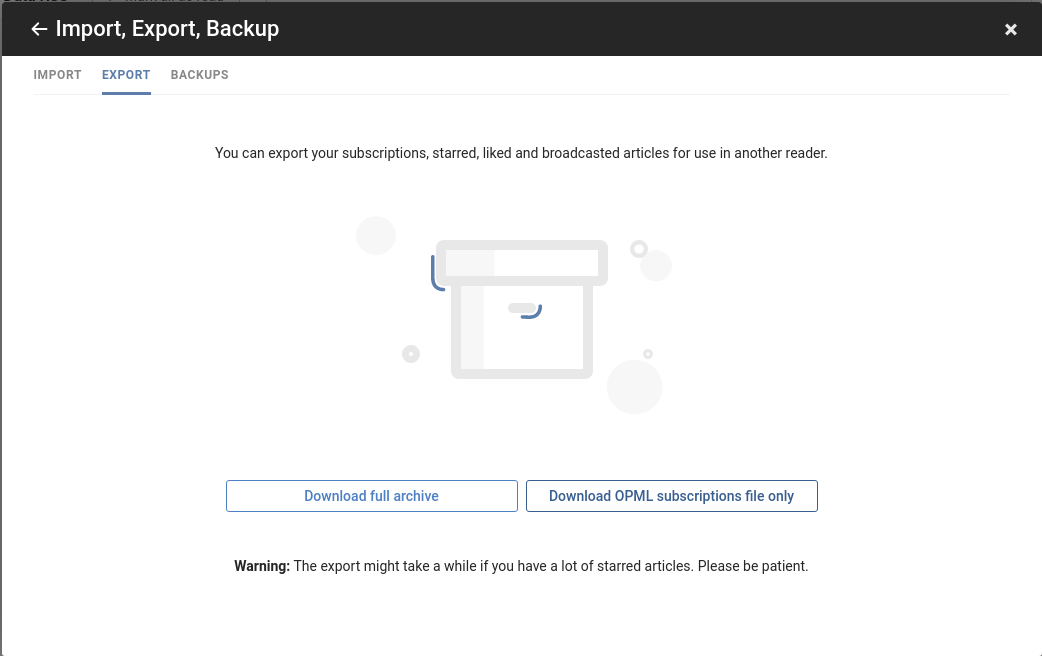

Another standard called OPML lets users export and import their Folders and subscriptions across RSS readers. OPML stands for Outline Processor Markup Language. As far as RSS goes, conventional wisdom seems to be that Google killed RSS when it shut down Google Reader, its own RSS reader. This is not true. RSS is alive and kicking, and all it takes to use it is finding a reader that works for you.

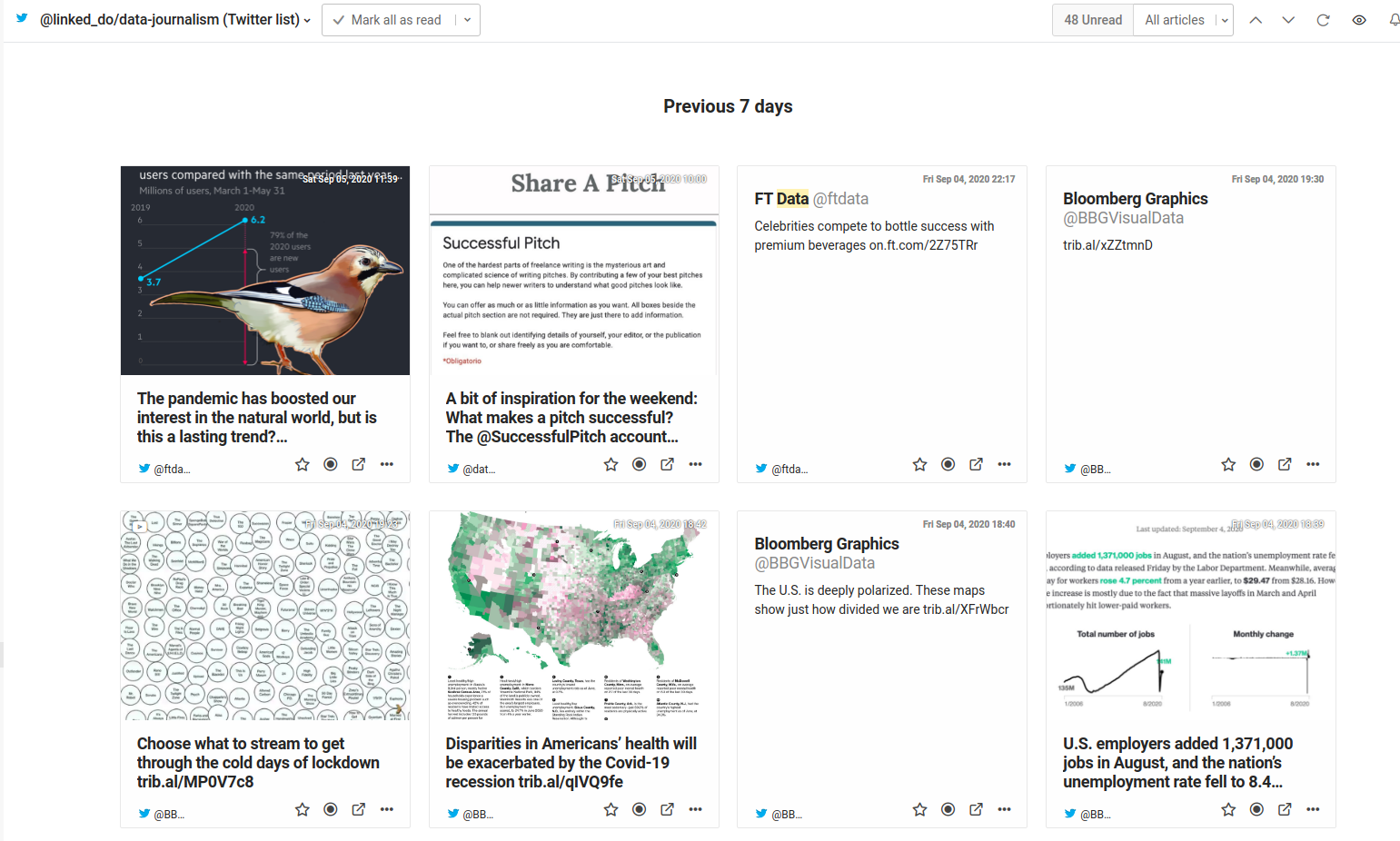

The idea of structuring your go-to sources in Topics via Folders can also be applied with Twitter lists — minus the portability aspect. Unfortunately, this means you will have to log in to both Twitter and your RSS reader to keep up with your Arts sources. Fortunately, there is a hack for that.

Some RSS readers let users import and view Twitter sources (plus Facebook Pages) as RSS Feeds, too. So you can curate your Topics independently, and still view them all in one place. This is invaluable. Not only does it let you use the RSS Reader as an inbox for Tweets you would otherwise miss, but it lets you use other functionality such as search, highlight etc.

Trust the process: why a structured approach to news reading is a good idea, and how to make it work

Using an RSS reader and doing some thinking around sources you care about and how to classify them is a solid first step. Now what? That does not really solve the “read later” issue. When reading news, we typically scroll over some items, read some fully, while we may want to return to others later. To accommodate this workflow, we need more than Folders: we need Categories.

Folders are a great tool to organise your subscriptions, but they are somewhat crude. Folders will show all new items for the subscriptions they contain. But they won’t let you categorise single items. This is useful for example if you want to keep custom collections of items applying ad-hoc criteria, as opposed to grouping based on the RSS source they come from. This is where Categories come in.

Although most readers offer some “Save for later”, “Star” or similar functionality, we advise against using it. Doing so cancels the effort of sorting sources in Categories, by dropping everything in one bucket again. Plus, this misses the distinction between “I want to read this later” and i “I’ve read it and it’s worth saving”.

Saving items per Category, and introducing at least two groups of items per Category, is a better approach. So if you have an “Arts” Folder, you need to create an “Arts – To Read” Category plus an “Arts – Save” Category. Luckily, RSS readers provide ways to do this. Inoreader calls these Categories Tags, Feedly calls them Boards. No matter.

Another Grouping you may want to add for your Categories is an Inbox. This will come in handy if your Reader supports search, enabling you to actively filter your subscriptions for specific keywords. Directing the results of your active searches to an Inbox for each Category helps you stay on top specific things you care about.

As a rule, you should think about actions you want to perform with news items that pique your interest and create a Category for each action. This way you will know what is where at any given point in time. That said, however, it’s still up to you to actually follow up on your intent, and read or save your news items.

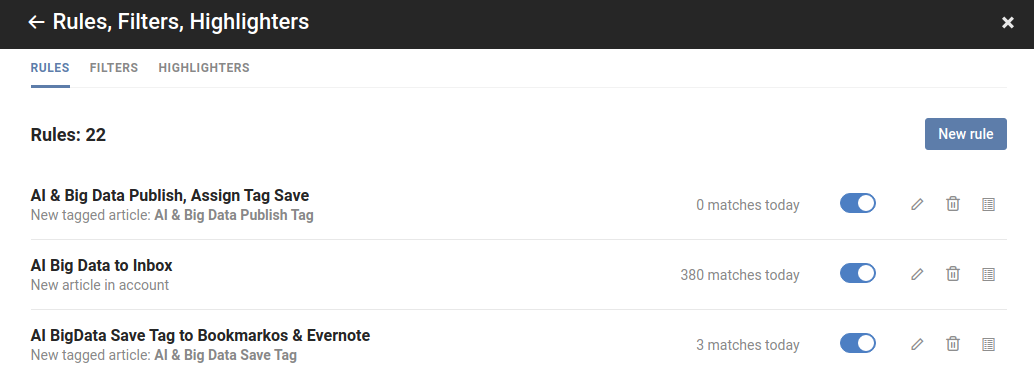

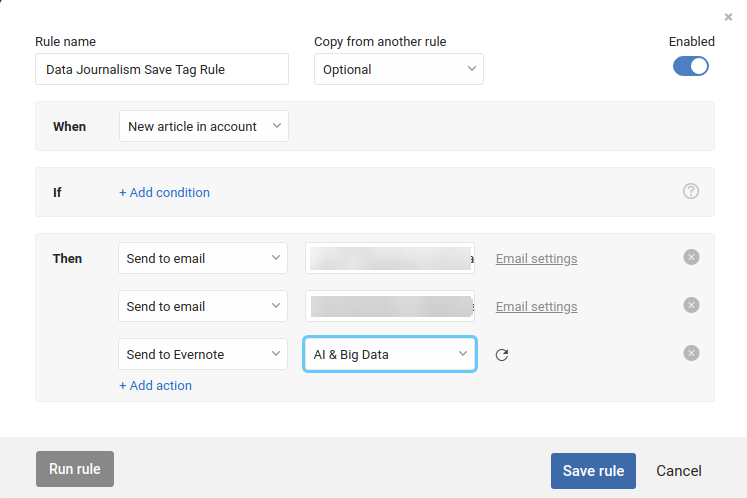

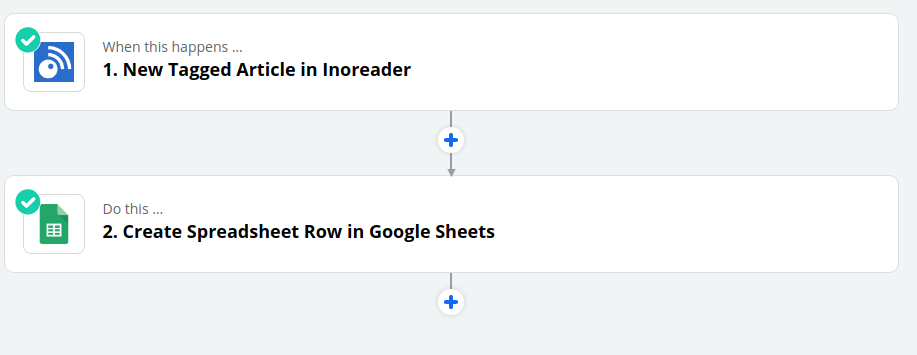

Some advanced Readers may help there, by automating things for you. For example, by defining rules that trigger when you put items in groupings, and perform actions. So if you put an item in your “Arts – Save” grouping, the item will be automatically saved. This brings us to the topic of saving items. Before that, one last point.

Your RSS Reader is your news inbox. Fine-grained and powerful as it is, you don’t want items hanging around your inbox for permanent storage. There are other tools to help with that. If you’ve made sure items are properly saved for the long term where they should be, you should clean your Groupings from time to time. Otherwise, items will start piling, and you will lose track.

Own the data: it don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that save button

Getting your incoming news sorted is only half the story. The other half is being able to archive them in a way that enables you to find what you’re looking for. Many people these days use note-taking applications like Evernote or Onenote to do this. Their main benefits are integration and full-text search.

Many Readers support note-taking applications, making saving items a one-click action. In addition, items saved in those applications get stored in their entirety, which means you can retrieve them by searching for any word contained in its body.

There are also some serious drawbacks, however — lock-in and opacity. These applications make it hard to import and export items saved in them in a portable format. In addition, you may get access to the content, but the source is obscured: the link to the original item becomes a second-class citizen.

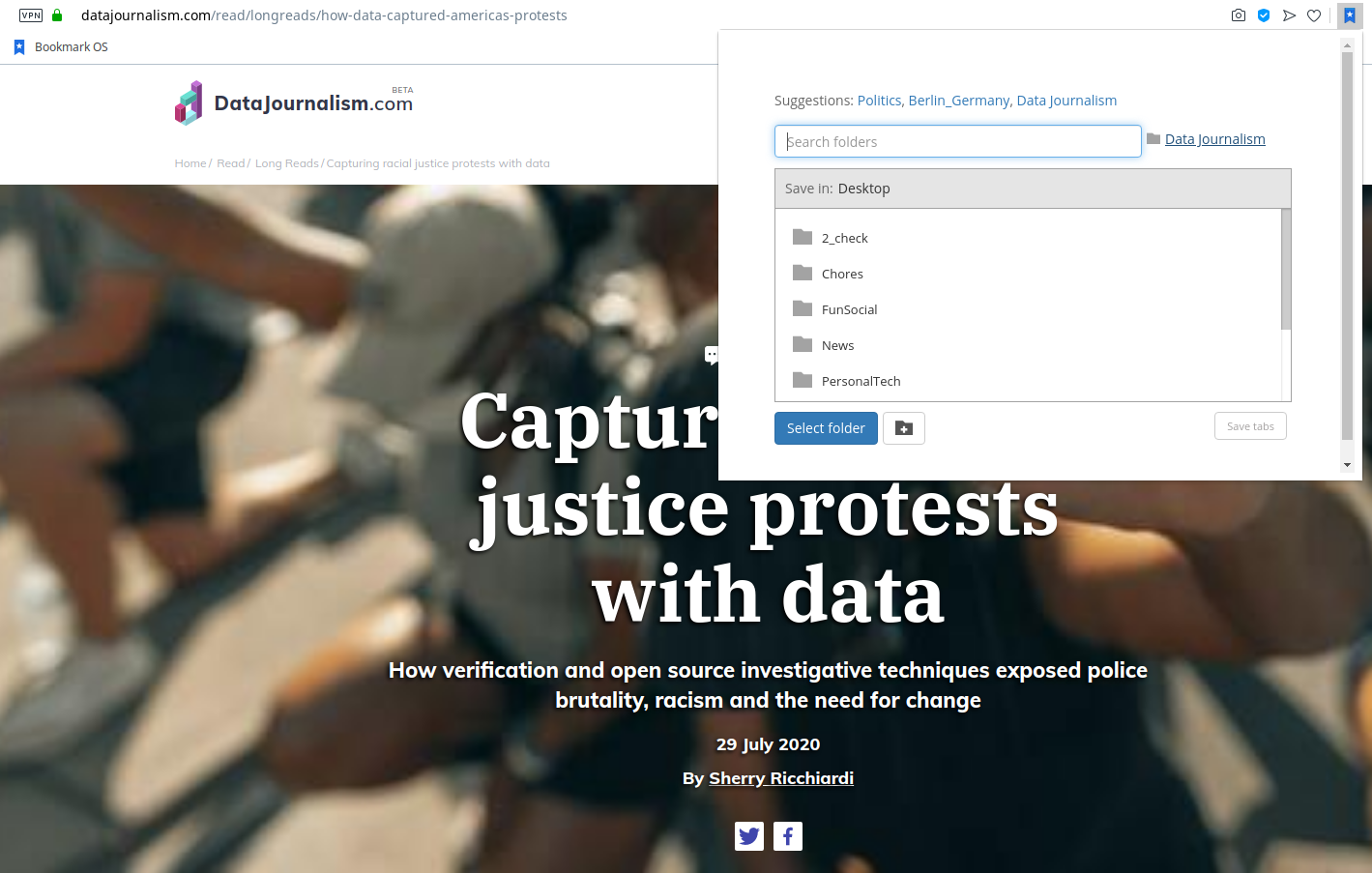

The alternative is to use something considered rather passe these days: Bookmarks. Bookmarks are a standard way of saving links. All browsers have integrated bookmark functionality, and the format for saving bookmarks is standardised, making it easy to import/export between services.

Storing bookmarks goes beyond links: additional information such as title, tags, comments, date added/modified is supported. What’s more, since anything can have a URL, from a file to an image to a web page, anything can be saved as a bookmark.

The most obvious issue with Bookmarks is the fact that they are local to each browser. However, there are ways around this. One way is to use browser sync services. Browsers today enable users to create accounts. Using them, users can save all their bookmarks across devices in a central location, if they always use the same browser, and are logged in.

3rd party, standards-based bookmark services also exist. Delicious, acquired by Pinboard, was the most well-known example of such a service. Diigo has followed its footsteps, BookmarkOS and Raindrop are others. Each has strengths and weaknesses, but their core offering is similar: save anything, anywhere (via browser extensions or mobile apps), annotate with text and tags, store in a standard format.

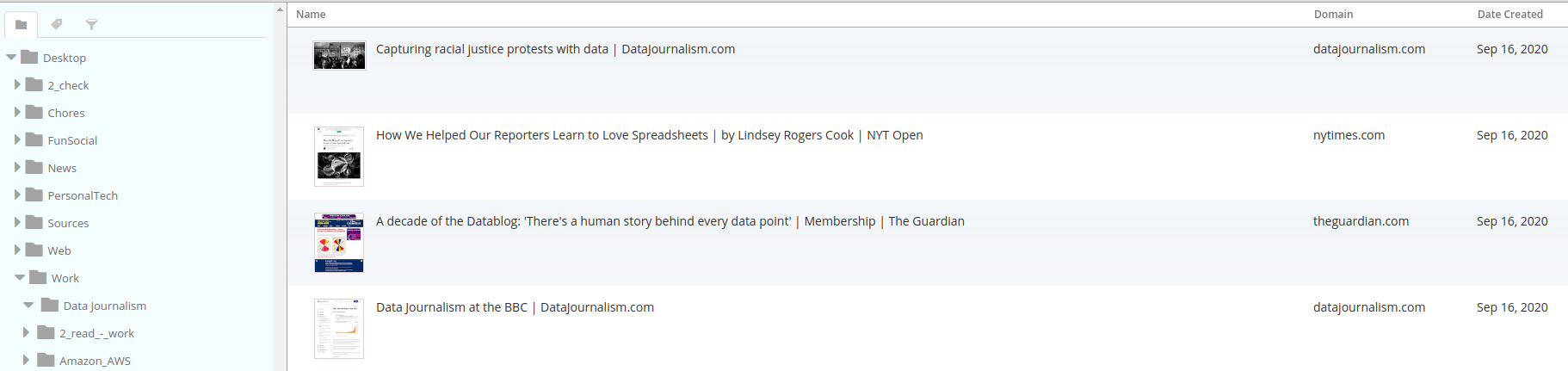

To get the best of both worlds, saving items in both a note-taking application AND a bookmark service is recommended (though Raindrop may be able to cover both bases). Bookmarks and notes can also be organised in Folders. In order to have a consistent way of classifying items across systems, the Folder structure created for reading should be replicated in your item saving application(s) of choice.

A word of caution regarding Folder structure. Bookmarking allows users to create arbitrarily deep Folder hierarchies. For example, you can have a “Painting” Folder nested within “Arts”. As a rule, note-taking applications do not. They only support a one-level structure — no sub-Folders. If you use them, you will have to lump your otherwise fine-grained hierarchies in big buckets.

Again, some Readers offer automation, so that putting an item in a Grouping, and creating a rule for it, will save it in corresponding Folders in your Storage application(s) of choice.

Annotate, save, share, repeat: adding your personal touch, sharing with the world

As great as RSS Readers may be, some items will always come your way via serendipitous browsing, or social media finds. That’s fine, as long as they all end up in the same place – your Storage application(s) of choice. To achieve this, you need to:

- Make your Storage application(s) easy to access

- Intentionally open items you want to save

- Ideally, annotate items you save

Making your Storage application(s) easy to access typically comes down to a browser extension. If your application(s) offers browser extensions, this makes it super easy to store anything at the click of a button. Mobile apps help too, if you don’t want to use a mobile browser. Having browser extensions and mobile apps should be among the criteria for choosing Storage application(s) – or any application really.

Whatever you are using to browse news besides your RSS Reader, whether it’s a browser or a native mobile application, there is always a way of getting the link to the item you are interested in. If you can do that, it means you can also open that link in a browser, and use your Storage application browser extension to save the item. Or you should be able to use the Share functionality on your mobile app to either send directly to your Storage application(s), or send via email.

Another word of warning here. Most social media offer some kind of bookmarking / save later functionality. Don’t use it. It will lock you in (you can only save items you come across on that platform) and you will lose track asnavigating your saved items is chaotic.

If you are in a mobile application for example, you can store an item directly via sharing on your Storage application, or even email. Many applications accept incoming items via email.

Better yet: you can use your RSS Reader to save the item in the Grouping it belongs to. This works in 2 ways. Besides keeping all your reading in your RSS Reader, if you have added automation to your Groupings, the item will be processed without further action on your side.

Storage applications also let users add annotations, in addition to the item itself. Even though you may not always be willing or able to do this, if you have the time for it, it does add value. Some typically useful annotations are tags and notes.

Tags are the most relevant and characteristic keywords for an item. Adding tags to items works both as a way of quickly finding out what items are about, as well as a way of finding related items. Items with similar tags normally refer to similar topics, and tagging makes browsing across them easier.

Notes are free-text notes which can be shaped to your liking. One way of using notes is to store summaries of the gist of an item’s content. This does not necessarily have to be deep and thoughtful, although making it so does help. Summaries, however, can be as simple as adding your personal touch to a link you would share on social media.

Thinking about summaries this way opens up an array of options. One simple option is to simply save summaries for your own use, as a note to self. Another option, if you would like to share your summaries with the world, is to actually use your summaries to post on social media. The hard part is writing it, in a way, how to store and share is again a matter of automation.

Reusing your summary can be as manual as copy-pasting it from your RSS Reader or Storage application browser extension to your social media sharing application, or as savvy as using automation facilities in your Reader to make sure your annotations are picked up and stored in all the right places — including being shared on social media.

Save for posterity, interoperate, automate: standards are your friend

This is just the beginning of what you can do with your news items. Once you start thinking about consuming and storing your news in a structured way, and leveraging standards and automation, the sky is the limit.

We already referred to some key standards: RSS, which lets you subscribe to any news source. OPML, which lets you use your subscriptions in any RSS Reader. Bookmarks, which lets you import and export your items to and from any bookmark application.

If you have mastered these techniques, applications and formats, and you are ready to explore more options, there is one more format, and some applications that can help. The format is CSV, the common denominator for working with data. The applications are back-end integration services like Zapier or IFTTT, which can help capture more data and connect applications to one another.

Many applications today make their APIs available on integration services. You can think of APIs as ways of getting notifications and accessing functionality in applications. For example, scrolling past an item in a RSS Reader triggers an API notification. Opening an item triggers another notification. Calling a Storage application’s API can tell the application to store an item.

Normally, it takes programming skills to use these APIs. But integration services make this functionality available to everyone. They require a fee to use (even though free tiers exist), and they still need time, and advanced application understanding, for things to work. What they offer in return, however, is remarkable: the ability to integrate disparate applications.

Being able to implement hacks such as “Store items I save in that Grouping in my RSS Reader, in this Folder in my Storage application” makes life easier. But there’s more to integration than this: saving data for future use.

How would you like to be able to keep track of items you read versus items you skip, times of access, sources, or how you annotate them? That’s the kind of thing social media platforms do, which is why they know so much about you. But with the right tools and some savvy, so could you.

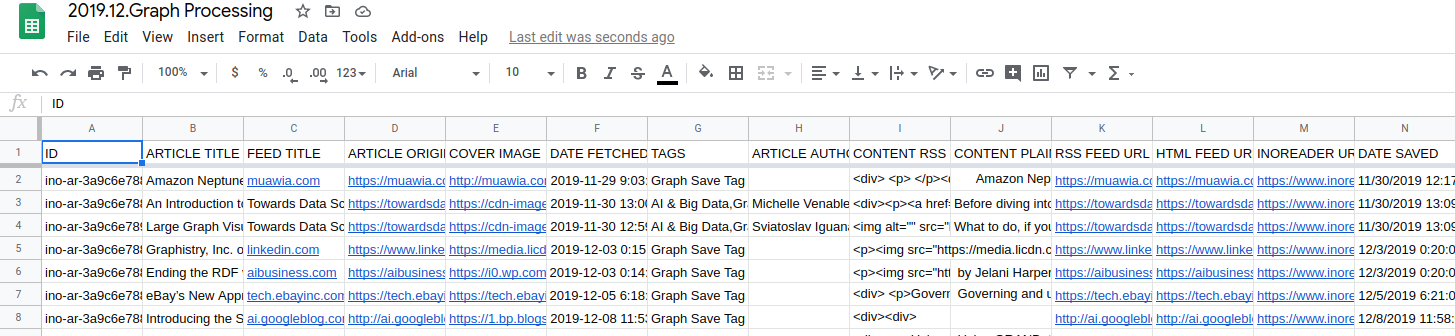

You can tap into your RSS Reader API, and store that data in Google Sheets. From there, exporting to CSV, and having that data in a portable format is easy. What can you use the data for? To train a machine learning algorithm that can annotate the way you do, for example. Or to browse, and learn from, your news reading patterns.

One step at a time, in it for the long run

This may sound like a lot. Frankly, it is. But you should not let it intimidate you, as much as you should not expect to go from zero to hero in a day. This approach has been honed over years and distils research and practical knowledge across a number of domains. Take one step at a time. The approach is built in a way that allows you to do this. Some structure is better than none. Some tooling is better than none.

Progressively, you will start becoming more familiar with the principles, and more comfortable with the tools. Of course, you can tweak to your own liking. The point is to find something that works for you. As you will find your own pace and way of doing things, one last word of warning: do not get carried away. The approach and the tools will enable you to process much more information than you thought was possible. You need to know where to draw the line. Information overload is a very real risk to your well-being. Sometimes, just because you can do something, does not mean it’s a good idea to do it. Remember – the point is to find something that works for you.