Pragmatic AI adoption: From AI literacy to futures literacy

What does it mean to be pragmatic about AI adoption, while staying true to the values and mission driving people and organizations?

When Elisa Lindinger decided to talk about AI, her intention was to say what she had to say once, and then move on with her life without having anyone ask about AI ever again. The plan backfired heavily, but somehow, that turned into a good thing.

Lindinger is the Co-founder of SUPERRR, an independent non-profit organization. SUPERRR was created to serve the thesis is that digital policy is social policy, and it needs bold visions and feminist values.

Like most other individuals and organizations today, Lindinger’s inbox has been flooded with new invitations every day. Invitations to discuss AI, to facilitate workshops on feminist AI, or the inevitable coaching offer to finally learn how to prompt properly.

This made Lindinger feel that other topics that are just as crucial are disappearing from the conversation. Her post, “AI and Unlikelihood“, was an attempt to situate how the people at SUPERRR view the phenomenon of AI, and why they believe it’s essential to return our attention to other topics as well.

What happened instead was that SUPERRR’s post got viral on LinkedIn, reigniting the topic of AI and stealing the limelight. An algorithmic glitch? Perhaps. But SUPERRR’s stance of rejecting the narrative of blind adoption of generative AI resonated with many people.

We met with Lindinger to explore the nuance behind what some might superficially call a Luddite approach, and to talk about setting priorities right, imagining futures people want to live in, and how to go from AI literacy to futures literacy. With cracks in the AI narrative beginning to show, the backdrop could not be more timely.

AI – what for?

Lindinger is prehistoric archaeologist by training, a topic that she describes as very niche as well as very data-driven. A life-long tinkerer, Lindinger brought that approach to her acquaintance with statistics, data science, databases, and machine learning. She gradually shifted from her field to computer science, eventually leaving academia to chase her passion for civil society work.

Through stints at organizations such as the Open Knowledge Foundation Germany, Lindinger got to work on open data, open source, and open government initiatives. While she enjoyed this work, there was one thing that kept bugging her: what for? What is the goal of using those tools?

“Openness is not a goal for me. It’s a tool. It’s a value that we have to apply for something. That is the reason why my co-founder Julia Kloiber and I decided we wanted to found our own organization. Because our ideas of advancing a more just and equitable society – we didn’t really have a space in an existing organization where we could do that”, Lindinger said.

This same question – “what for” – is at the heart of Lindinger’s AI manifesto for SUPERRR. Lindinger has worked on machine learning projects in the past, and has also been keeping up with the field out of personal interest. Her skepticism comes from a place of knowledge. As she puts it – “I’m not against the mathematics behind it”.

The reason Lindinger felt compelled to clear the air on SUPERRR’s stance towards AI is that like other domains, in civil society, too, AI has gotten too big to ignore. At some point, Lindinger decided it would be good to explain why they are politely passing on most AI-related invites.

Knowing what we talk about, when we talk about AI

It all begins by knowing what we talk about when we talk about AI. In the introduction to their book Snake Oil, Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor propose a thought experiment: Imagine that instead of talking about bicycles, trains, cars or aeroplanes, we referred to them all as ‘vehicles.’

Without the specificity of language, we would be unable to describe so many traffic problems, let alone develop effective solutions for them. The discourse on AI is similar, with just one label lumping together a whole range of technical approaches and applications.

As Lindinger notes, some of these approaches are useful and well researched. Other approaches can pose major risks to society, propose non-deterministic approaches and are therefore difficult to assess in terms of their impact. We can’t talk meaningfully about AI when it can mean everything (and nothing).

Once you shift from talking about specific applications, which is totally valid, to just talking about AI as kind of a placeholder, the discourse tends to shift. People start imagining omnipotent AI, the AI singularity, and the conversation becomes “Terminator all the way down” as Lindinger put it. So the term AI itself and the narrative around it are not helping to have a nuanced discussion.

Nowadays, when people talk about AI, most of the time they refer to generative AI: transformer-based, data-, water- and power-hungry deep learning approaches. Clearly, that’s not all there is to AI. But GenAI has hijacked the discourse and people’s attention, driving the AI hype.

AI hype and harms

The hype around AI serves a purpose, Lindinger claims: It lets people make grand claims about its benefits without seriously confronting its harms. Those harms are well-documented, but sidelined for what Lindinger posits has been mostly empty promises.

For example, the AI industry has a devastating impact on the environment and climate; and though there is some talk of this, there’s still a focus on developing infrastructure such as resource-hungry data centres. However, the damage that AI is causing today is overshadowed by promises for the future: ‘AI can help cure cancer, or offer free global education – so we need data centers’.

AI also amplifies injustice in the world, starting with the invisible labour that is fueling the tech hype, which languages and knowledge bases are considered valuable and useful, and ending with who is visible in the outputs of AI and how. And let’s not forget massive copyright breaches and model collapse.

If we follow the AI hype, our vision of the future becomes a distorted image of the past, an ‘AI Empire’ crafted by tech bros, Lindinger warns. Hype-based tactics may have reached new heights with AI, but it’s nothing new for Big Tech, she goes on to add.

“I come from the tinkerer and hacker culture. For me, technology is ultimately enabling. It’s something that is fascinating, fun, something I want to understand. The whole fear of missing out narrative is cutting all of these things short.

Whenever a sales pitch wants to put me under pressure, my alarm bells go off. I think there is something that you have to hide because you don’t want me to have a closer look” Lindinger said.

Is AI really adding value?

Lindinger describes the enthusiasm surrounding AI as Labubu, but for boardroom executives – it’s about being part of the hype. There are anecdotes of executives pushing organizations to “do something with AI”, and published accounts of organizations going all-in on AI – and then often U-turning with little fanfare.

As researchers from the Stanford Social Media Lab and BetterUp Labs share on HBR, while workers are largely following mandates to embrace the technology, few are seeing it create real value. For instance, the number of companies with fully AI-led processes nearly doubled in 2024, while AI use has likewise doubled at work since 2023.

How exactly this impacts productivity and profitability for organizations, however, is up for debate.

A recent report from the MIT Media Lab claims that 95% of organizations see no measurable return on their investment in these technologies. However, critics claim that the report’s methodology is flawed and doesn’t offer conclusive evidence. Also, they add, the report only addresses proof of concept projects, which by their nature cannot be expected to have a high ROI.

Other reports, such as KcKinsey’s “The state of AI” show different results. Compared with early 2024, larger shares of respondents say that their organizations’ GenAI use cases have increased revenue as well as brought meaningful cost reductions within the business units deploying them. Of course, how exactly that should be interpreted is also up for debate, as recent consultancy layoffs show.

Drawing the line

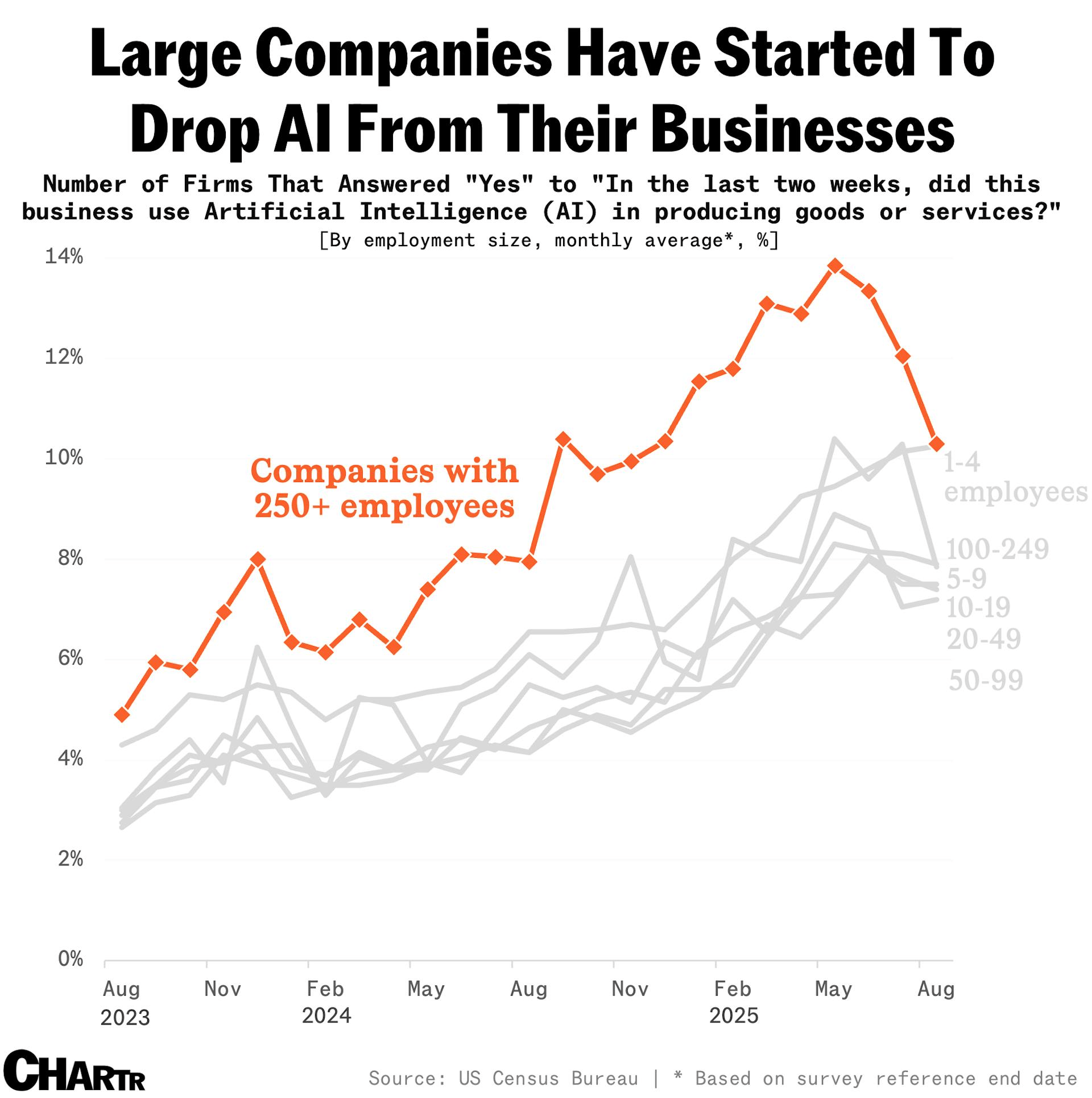

Either way, the tide may be turning. For the first time since tracking began, large enterprises are reducing their GenAI adoption. The U.S. Census Bureau reports that AI use among companies with 250+ employees fell from 14% to 12% since June 2025.

This may be a symptom of the core issue revealed by the MIT report – a classic case of what AI Consultant Paul Ferguson calls “Technology Push” vs “Market Pull”. Technology Push is – “we have AI, what can we do?” while Market Pull is – “we have problem X, can AI help”?

FOMO and the notion that this is inevitable are never a good basis for decision-making, Lindinger notes. So we should pause for a moment and ask: What do we want? Not: What do we have to do.

So where should organizations draw the line? What types of use cases are the right ones for AI?

For Lindinger, using AI only works for secondary functions. Taking translation as an example, it’s fine to use AI to get a quick idea of what something is about. But to present work results in different languages, or to generate original research, art and content, SUPERRR works with professionals.

“When it comes to translating our values into the products that we publish, we work with experts. We work with artists. And that is where we, as an organization, draw the line. The other reason of course is compliance. We work with data from partners, and funneling those into applications where we don’t know what exactly happens with the data is sheer horror”, Lindinger said.

AI and workslop

When describing her experience of working with AI, Lindinger referred to the process of having to constantly curate the results. For example, there are certain terms that SUPERRR refrains from using. When using LLMs for translation, they will sneak unwanted terms back in the text. Then someone has to go through the text and edit it.

Lindinger believes that’s not worth it – it’s more work actually than working with a translator who just knows their craft. Lindinger touched on something people are widely identifying, and now has a name, too: “workslop“.

As the people who coined the term note, the insidious effect of workslop is that it shifts the burden of the work downstream, requiring the receiver to interpret, correct, or redo the work. This has negative effects beyond the effort required to fix things. Unsurprisingly, low-effort AI-generated work makes people think less of those who pass it on.

For example, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella received criticism for sharing what seemed like AI-generated posts on X. But there is more than the fear of backlash that should keep people and organizations from outsourcing core functions to AI.

It’s about more than losing one’s voice. Studies on “cognitive offloading” (using GPS, calculators, or AI for thinking tasks) show measurable atrophy when the brain isn’t exercised. There is a price to pay for what Carl Jung called “Unearned Knowledge“.

AI literacy

Having reviewed all that, we return to the concept of AI literacy: knowing enough about AI to be able to exercise informed judgement. But what does AI Literacy entail exactly, and how do we get there?

The concept of literacy is not new in in the digital field, Lindinger points out. There are precedents such as data literacy or digital literacy, and there are some shared takeaways from these different discussions. She believes the literacy conversation puts a lot of pressure on the individual, and that’s not fair.

“The first step to be AI literate would be able to see whether or what kind of AI you’re using. We have an accountability problem on the provider side that individuals in their in their workplaces are meant to compensate for with AI literacy. And I think that is actually setting them up to lose. I’m not sure that is also bringing us forward, towards AI being deployed in a more rights-conforming way”, Lindinger said.

For Lindinger, ideally, the tools that people use should bear some kind of labeling to denote the degree and type of automation they use. And people should also, first and foremost, be educated on basic concepts of statistics and probability to build a foundation for AI literacy.

From AI literacy to futures literacy

Lindinger thinks the Six Pillars of AI Literacy is a good framework for AI literacy, with the emphasis on creation and tinkering. However, she’d rather leave AI literacy to people who focus on AI. What she sees as the strategic goal for SUPERRR is futuring: working with people to imagine futures they want to live in.

“We are so used to living in highly structured environments that do not really give us a space to be creative, to break free from the things that we have learned and imagine something radically new that we then can figure out whether we can actually reach and work towards it. So this is what we want to work more on. We call it futures literacy.

We use the term literacy here as well. Of course, AI plays a role in that because right now, hardly anyone can imagine a future without AI. What we do is to question – yeah, but what for? It doesn’t have to be there. You can make the decision. What would your decision look like?” Lindinger concluded.

In the short term, Lindinger believes that fundamental matters such as social cohesion or the protection of children online are very important topics that we should be focusing on and have nothing to do with AI.

Addressing questions such as – what kind of safeguards can we come up with? What kind of designs can we come up with for digital systems, online platforms, all the technologies that surround us, to make them work in our interest? These are very much low tech questions, involving people and their disregard for each other. But the questions are important, and low tech has a charm in itself.